Over the weekend, I attended The World Transformed gathering in Hulme, Manchester, and it’s been a phenomenal learning experience. The agenda was packed with housing panels and discussions – ‘Gentrification is Class War’, ‘Winning Rent Controls’, ‘Rent Strike as a Weapon’, to name a few. There were some common themes that will surprise absolutely no one working on housing right now:

- Social housing and temporary accommodation in Britain and Ireland is in a ‘disastrous’ state

- Public housing tenants are expected to be grateful for whatever’s provided

- Tenants are isolated – which is a tactic not an outcome

- Tenants are mobilising, resistance is growing, and history matters

There are so many crucial issues to explore here – the intersections of race, class, and gender in the housing ‘crisis’*; the historical roots of tenant isolation; the role of mutual aid networks – and I hope to get to them in future posts. For this post, I want to focus on the last theme: that tenants are mobilising. Not least because it speaks directly to our Save Our Homes LS26 campaign. Specifically, the question of: who is doing the fighting, and why?

*not a crisis when it’s been the norm for more than a century

Leading and sustaining tenant resistance

Across the weekend, the prominent role women have played in leading or sustaining the long fight for housing justice was very clear, both historically and today.

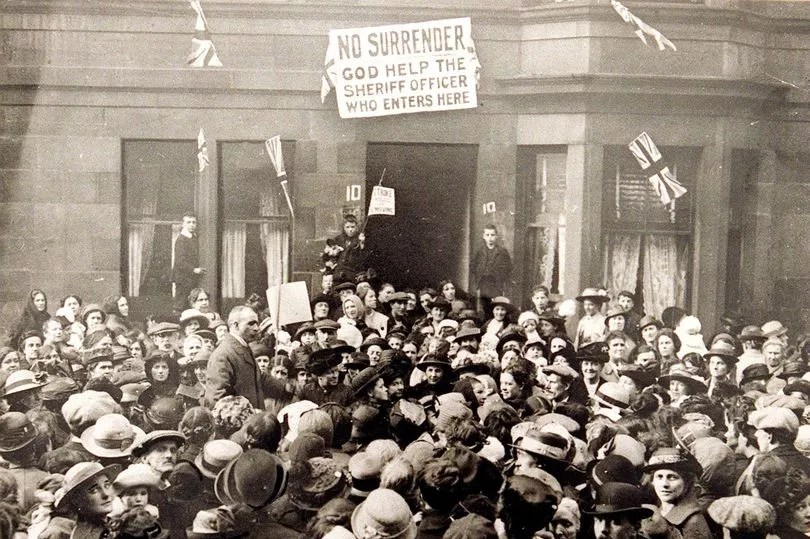

First, the women-led Glasgow Rent strikes of 1915 were a frequent reference point. Panellists on the ‘Winning Rent Controls’ discussion cited these strikes as the prime example of what mass action could achieve today. In Saturday’s ‘The Rent Strike as a Weapon’ session, René Moya of the Los Angeles Tenants Union said they even have the 1915 Glasgow activists printed on t-shirts as inspiration to members. (Unsurprisingly, it’s also the first case historical case study in EVICTION, my book about Save Our Homes LS26 and the long housing crisis).

In short, this strike – led by Mary Barbour, Helen Crawfurd, and the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association – saw 25,000 tenants withhold rent from war-profiteering landlords who massively hiked rents and evicted with impunity, particularly across 1914-1915. Resistance began at the grassroots, with women establishing neighbourhood lookouts for bailiffs and pelting them with flour and wet washing to prevent evictions. Then they took it to the courts. When landlords tried to prosecute a handful of tenants, thousands protested outside – “Mrs Barbour’s Army”, as they were nicknamed.

Similar but smaller scale strikes and protests were happening across Britain at the same time (including Leeds!), but it was the Glasgow mass action that forced the government into changing the law. The 1915 Rent Act froze rents at pre-war levels and making eviction harder. A huge win!

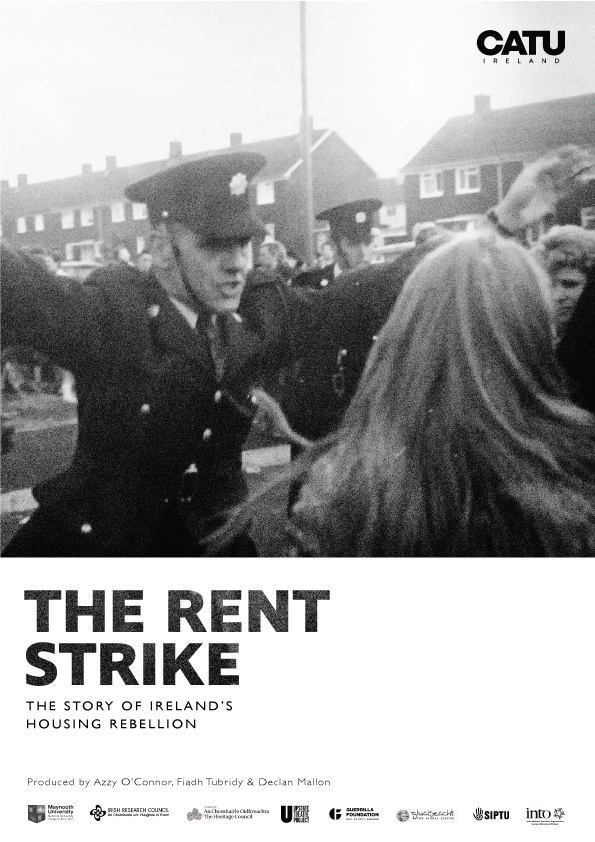

Elsewhere in the TWT festival, I learnt about an equally impactful mass strike in 1970s Ireland. On Saturday evening, the Irish tenants’ union CATU screened ‘The Rent Strike’ documentary, focusing on the 1970-1973 mass rent strike across the country. This movement emerged following the government’s unrelenting implementation of deeply unjust rent rises. Tenants formed the National Association of Tenant Organisations (NATO), which went on to lead 350,000 striking social tenants into victory: rent reductions and the recognition of NATO as their official representative.

While men like Matt Larkin Snr, head of NATO, led negotiations and dominated headlines, CATU’s oral history interviewees revealed that it was the women who went out every week, collecting rents and subs, women ‘who were at the barricades, women out there with their prams’. They knew the neighbours, knew the neighbourhoods, shared support, resources and information. They kept it going.

Then, at the ‘Public Housing for All’ panel on Sunday, Manchester-based social housing tenant and activist Thirza Amina Asanga-Rae shared her story of being forced into action. She’d moved into a 2-bed terraced social house in Moss Side (with two sons and one daughter, she had to sleep in the living room). Urgent repairs went ignored and unfixed for years. When the housing association eventually took action, the repair job was so shoddy that, shortly afterwards, parts of ceiling fell on her head while she was cooking in the kitchen. Thankfully her children were upstairs at the time.

Enough was enough. Asanga-Rae joined GMTU as an organiser and now sits on the Manchester Social Housing Board Commission as well as standing as a local Green Party candidate – affecting change for other social housing tenants like herself.

Three examples, each around 50 years apart – yet with similar patterns: women facing the full force of housing insecurity and having to fight for basic rights and decent living conditions. To this list I could add the East End rent strikes in the late 1930s, or those featured in EVICTION: the Abercromby rent strikes in Liverpool in 1968-9, the Kirkby rent strikes in the early 1970s, and the mass protests in the 2010s for the New Era Estate in Hoxton and Focus E15 in Newham. Not forgetting our Save Our Homes LS26 fight in Leeds.

All women led or women sustained. Many of them intersectional; fights that have reflected the compound and distinct challenges that housing precarity inflicts on working-class women, women of colour, migrant women, and women with disabilities (I’ll return to those intersections in future writing).

Why women?

This pattern of leadership is part of a tradition of women’s political struggles. Working-class women, time and again, organising in kitchens, living rooms, playgrounds, and gardens before taking action to the streets. They do this because they must, as women face the full force of housing insecurity.

First, there are the economic pressures. Women are twice as likely to manage household budgeting in heterosexual relationships, which means when rents spike or eviction notices arrive, it’s women scrambling to make the numbers work. Women pay a larger proportion of their income as rent, so they feel every increase more acutely. And nowhere in England can a single woman on average wages afford to privately rent – trapping many in unwanted shared arrangements or unsafe relationships, especially when domestic violence refuges remain insufficient, underfunded, or completely inaccessible. These economic realities aren’t new – in fact, many (like the gender pay gap) were far worse in the past.

But it goes deeper than household budgets. As I show in EVICTION, housing insecurity itself is additional care work that has always landed disproportionately on women: searching for new homes that meet all family needs, managing school disruptions, re-settling children, switching healthcare providers, endless letting agent paperwork, and the physical labour of packing up an entire household. In other words, just another set of chores on top of the cooking, cleaning, and caring women already shoulder.

And to compound those challenges, rent hikes and evictions don’t just upend individual households, they destroy everyday mutual aid networks – the safety nets – that women sustain and entire communities depends on. The neighbour who picks up your kids from school when you’re running late. The friend down the street who lends you their car because you don’t have one. The elderly relative nearby who gets daily visits and company.

These cross-household care relationships – for children, for the elderly, for each other – are essential safety nets, especially when the state won’t provide or fund sufficient healthcare, childcare, elderly care, or secure housing to allow people to live with dignity.

When communities are dispersed through eviction or relocation, these networks are broken. But it’s no accident. Tenant isolation isn’t a side effect of housing policy – it’s by design (which was another key theme from TWT: landlords and housing managers consistently break up community networks, scatter so-called troublemakers, and thereby weaken collective resistance).

None of this is new. From the 1915 Glasgow strikes to the 1970s mass strikes in Ireland, to today’s campaigns, the pattern holds: housing insecurity is gendered, and women keep having to fight the same battles because the system keeps forcing families to live in abysmal conditions with unaffordable rents, or it keeps turfing them out and breaking communities apart. Thanks to the TWT, I now have even more examples to add to my growing historical list. (And I always welcome more – share them via the contact page!)

In the meantime, you can watch CATU’s “The Rent Strike” excellent documentary here for just £4.50: https://catuireland.org/documentary/