What links two tower blocks in Kirkby, Merseyside and a rural chocolate box cottage village 265 miles away in the Bridehead estate, Dorset?

Short answer: Faceless millionaire investor landlords and powerless tenants.

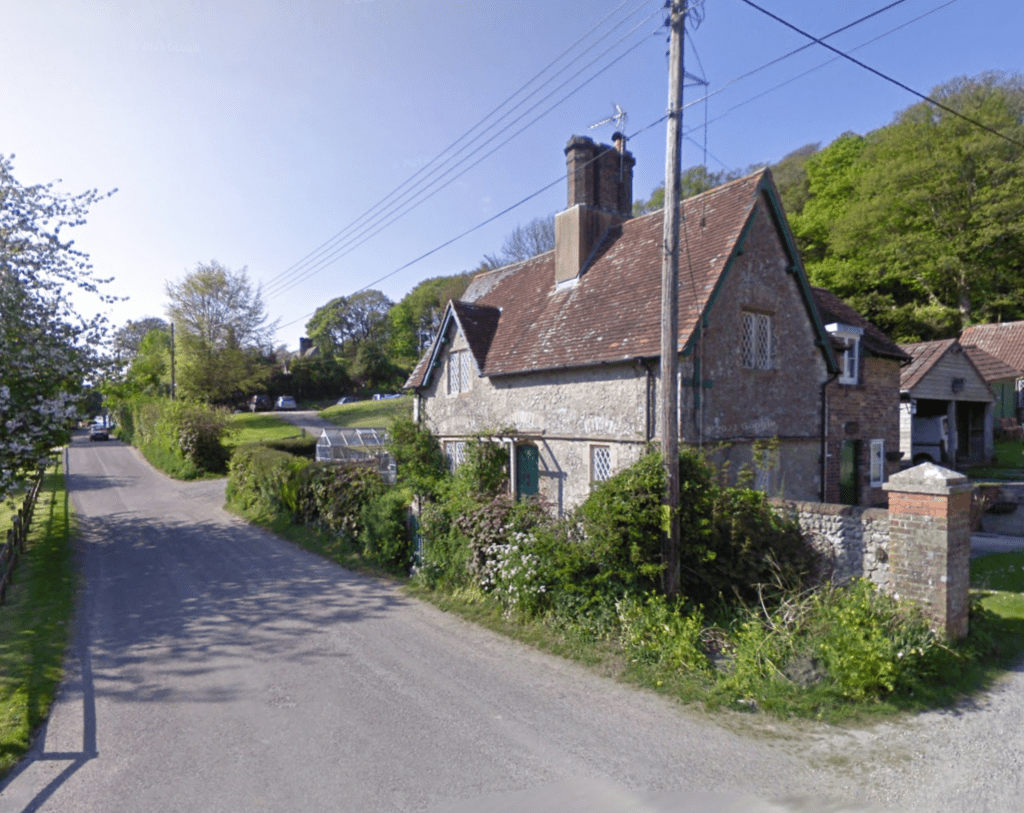

These two communities are seemingly worlds apart in socio-economic status and surroundings. The Kirkby community of renters and leaseholders live in two 15-storey tower blocks originally built in 1963 to house families relocated by slum clearances and then regenerated in 2007. The Littlebredy Dorset community live in picturesque cottages on a rural 2,000 acre private estate which includes a 19th century regency Manor House and pretty waterfall.

Yet both communities have no control over what happens to their homes and no idea who their landlords are.

Kirkby’s tower blocks are owned by a complex web of investors with a property portfolio worth hundreds of millions (if not billions) between them. Leaseholders and tenants in these towers are set to be mass evicted any day now as their homes are not fit to live in.

Littlebredy’s new landlord is a rural property specialist which, though only founded in 2016, owns land the size of Preston and £350 million worth of property assets. Littlebredy tenants have heard rumours eviction may be coming down the line; one resident has already been booted out.

As Save Our Homes LS26 learnt the hard way when we fought our mass eviction by Pemberstone across 2017-2022, tenant powerlessness and speculative investor unaccountability are baked-in features of Landlord Britain.

This blog post untangles some of the corporate interests sitting behind the Kirkby and Dorset investments to expose the utter absurdity of millionaires raking it in without having any apparent legal obligation to keep their tenants informed, secure and – in the case of Kirkby – even safe in their homes.

I’ve been following the Kirkby story for several weeks and each time it hits the news, I’ve ended up down a new research rabbit hole on Companies House. I’ll never get to the bottom, so here’s what I’ve learned so far.

The Kirkby Towers Story

Originally named Oak and Cedar Towers, Beech Rise, Willow Rise were commissioned by Liverpool Council and built along with six other blocks in 1963. The development was part of a massive council housebuilding programme in Kirkby designed to function as overspill for Liverpool slum clearances. Oak and Cedar Towers, and their six sister blocks, survived until the early 2000s when Knowsley council earmarked the area for regeneration. Refurbishment and renaming to Beech and Willow was completed in 2007. Flats apparently sold like hotcakes… But whoever bought them didn’t seem to care too much for building maintenance.

Less than two decades later, the towers’ private-rent and leaseholder tenants have been told they’ll finally be evicted after a drawn-out battle trying to get someone – landlords, the freeholders, the building owners, the management company – to take responsibility for addressing dangerous conditions that plague the towers. These conditions include: water leaks onto electricity boxes causing frequent black outs; out-of-service lifts trapping disabled residents inside the 15-storey buildings; malfunctioning fire alarm systems; holes in the walls; and chronic damp. Both buildings have been identified in a post-Grenfell inspection to have wooden cladding and wooden balconies, rendering them unsafe in the event of a fire.

Merseyside Fire and Rescue Service have issued multiple enforcement notices against the property over the years. Since at least 2020, MFRS have insisted that the building needs a “waking watch” of 24 hour patrols to alert residents to any fire. Knowsley Council had to implement that waking watch recently, costing around £400,000 so far, to ensure tenants could stay in their homes while some resolution was found.

An urgent sense of responsibility, however, seems not to have been shared by various corporations involved with the towers since refurbishment – a motley group of property investors shrouded by acronyms and meaningless gobbledegook: LPC [Legendary Property Company] Living, Parklands Management, Rockwell (FC100), Grainger, T R Marketing, and Dempster Management Services. Who sits behind these organisations?

LPC Living regenerated the estate around 2007, calling it the Parklands Scheme. Associated company Parklands Management was then appointed as the resident management company and took responsibility for contracting a management company (yes, a different one) to oversee maintenance, repairs and tenant issues. LPC Living and Parklands Management are associated because they shared top-level staff in common. Simon Ashdown, for example, is Director of LPC Living and also directed Parklands Management Company until 2014, tying LPC Living personnel to the company long after LPC completed the development in 2007.

One financial beneficiary of LPC Living Ltd is millionaire tycoon Pervaiz Naviede and the Guernsey-registered Pervaiz Naviede Trust – which owns LPC and had a property portfolio worth £58.3 million in 2015 when they sold it to another property investor Grainger. A PrivateEye database of tax-haven landowners shows Sarunas Properties Limited acquired the freehold of one of the tower block flats in 2010 – number 39 Willow Rise[1]. Sarunas Properties Ltd is owned by the Pervaiz Naviede Trust (PNT), suggesting that LPC/PNT/Naviede had financial interests in the tower blocks long after the end of the 2007 redevelopment.

So, what Willow and Beech Rise interests transferred to Grainger in the PNT property portfolio sale in 2015? Who knows! That’s the point. Distancing through faceless corporations makes doing business and generating profits a lot easier. As “publicity-shy” Naviede himself said in a rare interview back in 2008: ‘We do it [regenerations] because we make money out of it’. His longtime associate, then-LPC Chairman Warren Smith agreed: ‘We are not a charity’.

For its part, Grainger is the UK’s largest listed residential landlord and had a net income of £31.2 million in 2024. Google searches for “Grainger PLC” and “Willow Rise” or “Beech Rise” show the property investor has owned multiple flats in the two towers over the last decade (raising the question about whether developer LPC Living / The Pervaiz Naviede Trust might also have owned multiple flats which transferred to Grainger in the 2015 sale?). Anyhow, Grainger has been trying to auction many of them off for peanuts in recent years – presumably evicting tenants in the process.

If you think one multi-millionaire tycoon and one multi-million pound mega-landlord is enough for beleaguered residents, then I’m sorry to say that another property tycoon has links to the decrepit blocks. Billionaire Tory donor Vincent Tchenguiz and his equally wealthy brother Robert are named beneficiaries of Willow and Beech Rise’s “Head Lessor” company Rockwell (FC100) Ltd, registered in the Virgin Islands.

While Rockwell made noises about looking at its responsibility over maintenance and repairs, it concluded that the management company alone has “responsibility for managing the buildings and collecting and spending service charge money”. Hmm.

A head lessor is essentially the main landlord who holds the head lease and then grants subleases for individual units within that property. Lawhive describes a head lessor as ‘generally’ overseeing responsibilities typical of a usual landlord:

- The management of communal areas

- The collection of service charges

- The arrangement repairs and maintenance

If Rockwell declared it was not responsible for any management or maintenance, it seems to have just collected service charges. Nice ‘work’, if you can get it. And all perfectly legal.

The Tchenguiz property empire has form in shirking any moral duties over their properties, too. The Guardian reported in 2018 that Vincent, via another of his property companies, told residents of a Grenfell-style clad tower that they had to cough up £31,000 each for the cladding removal costs because his company, the freeholder of the cladded building, was not responsible. (Again, standard practice. Our ex-landlord Pemberstone tried to do the same to leaseholders in two of their cladded investment properties in Manchester in 2018-19… but lost the case at court).

So, what about the Kirkby towers’ contracted management company? That was, most recently, Dempster Management Services. Dempster terminated their own contract in May 2025 because of the scale of the work required (and, of course, because of the scandal erupting around the towers).

While Dempster came on board late in the game when the building was already in a dire state, they would have gone in with their eyes open and aware of the urgent to-do list. Yet, residents have been scathing about Dempster’s role in fixing clear hazards to life in the building. Resident Phil Noonan shared on Facebook in June that the company withdrew support for lift repairs at one point, until they were threatened with civil lawsuits.

For their part, building owners T R Marketing are ghosts. The BBC reported that the Salford-based company paid just £5,000 for the freehold in 2022 and have been dormant and silent since. Maybe they’re just embarrassed at getting such a duff deal. Maybe.

The Dorset story

The story of Littlebredy in Dorset is less convoluted. Residents of this tiny village have been thrown into turmoil after the 2,000 acre estate it sits on was sold to investment company Belport Ltd in May after being in the hands of one family for 200 years. There are 32 properties on the estate, 23 of them residential lets. Belport netted it all for around £30 million.

Both The Guardian and The Telegraph reported in June that the new owners booted out one tenant-of-21-years and unceremoniously padlocked access routes to some parts of the manor estate, cutting off a long-standing rambling route. (In response, around 60 protestors staged a Right to Roam trespass on the estate).

Requests for information and reassurance from the new landlord have so far been largely ignored. The company issued a mealy-mouthed statement denying plans for eviction and stating their intention to refurbish all of the homes in Littlebredy ‘which may entail disruption for tenants in some cases’. But this is not the reassurance that it sounds like.

While retrofitting outdated houses to modern energy standards is essential, Belport is a private equity property investor and will want to see decent returns on their assets and any refurbishments – returns that decades-old rolling tenancy agreements will not provide. To paraphrase LPC Living’s wisdom circa 2008: Belport is not a charity.

How might they go about this refurbishment? The company has already shown their hand by evicting one resident without concern for her long-established life and social connections in Littlebredy. The ex-tenant Christine McFadden, shared on social media that she felt ‘devastated about being chucked out of our home which we have rented for 21 years. Went there today to pick up a few bits and pieces and the guys from Belport were on the doorstep and we had to ask permission to go into our house to collect a few bits and pieces‘. Her old home is now an estate office.

Judge a landlord by their actions, not by their statements. Residents are right to fear rent hikes, the sale of their homes, the closure of permissive paths, and being unceremoniously evicted. It’s the property speculation operating model.

Nowhere safe from speculation

We know this all too well in Oulton. [**Plug warning**]… As I document in my new book Eviction: A Social History of Rent (out this September!), unnamed speculators hiding behind offshore companies bought my parents’ prefab estate for peanuts from the National Coal Board in the 1980s. Coal miner tenants had no idea who their landlord was. The company hiked rents and ignored urgent repairs while keeping their distance through managing agents – resulting in the mass flight of tenants who just couldn’t stand living in increasingly dire conditions.

These speculators then sold it on for profit to investment company Pemberstone in 1997, who ran it for more than 20 years through different management agencies and contractors. None of the ageing Airey prefab estate was structurally refurbished. Repair requests were ignored, sometimes for years at a time; contractors ever-changing and unconcerned with resident preferences for their homes. When the estate was declared essentially uninhabitable in 2021 due to (refurbishable) structural concerns, hundreds of low-income residents – including my parents – were evicted and the estate demolished.

So, you see, none of this is new. Speculator landlords have existed for decades – centuries even. The fact that they’ve historically overlapped with slum landlords is no coincidence. There are few ways a landlord of a low rent estate can make money without hiking rates, scrimping maintenance and/or evicting to redevelop.

While the condition of Willow Rise and Beech Rise towers is particularly grim, their story reflects the broader state of Britain’s housing emergency: poor property management resulting in uninhabitable, dangerous, living conditions. Tenants and leaseholders are left out on a limb, fighting to get basic safety work done. And for both Kirkby and Littlebredy, wildly rich investors sit far behind their lucrative properties, with layers of subsidiary companies, managing agents and contractors – distancing their accountability and raking in profits.

The end of the leaseholder system can’t come fast enough. But the ability of landlords to hide behind faceless companies also has to also end. Tenants need to be able to hold the individuals profiting from their rents or service charges to account – whether they are millionaire tycoons or accidental landlords. Otherwise, we’re only going to see more and more cases of property decline, raised rents and evictions. Kirkby and Littlebredy together show that nowhere – city or countryside – is safe from speculation.

Notes

[1] In further ‘rabbit hole’ discoveries, it turns out 39 Willow Rise was sold for £94,770 in March 2007, the year of regeneration… and then for just £46,515 in 2015. Housemetric highlights that this sold price has been marked by Land Registry as Category B: Additional Price Paid Entry, which could be due to a variety of reasons ‘such as the sale being a buy-to-let purchase, a repossession or a transfer to a limited company. When Land Registry suspects that a sale does not reflect full market value (e.g. part-ownership or right to buy), these transactions can be flagged as well’. Did Sarunas Properties Ltd sell or transfer it in 2015? Whoever owns it they don’t want it any more; 39 Willow Rise was due to be auctioned on 25 July 2025 but has been withdrawn.

Jess, Grainger used to manage our estate some years ago. They had a very in your face attitude when it came to annual gas checks. They would say in their letters. ” we see you have refused our operative entry to your property. Be aware this constitutes …..whatever”. I can’t guarantee the wording is correct but that is the gist. I would speak to the contractor and he would say our check wasn’t due for a couple of months yet. Yours sincerely Mavis

Yahoo Mail: Search, organise, conquer

LikeLike

Hi Mavis! That does not surprise me one bit. It’s just such a rude and aggressive approach and shows what they think of tenants. Grainger were there around the time when Mum and Dad moved in and I remember they used to charge ridiculous amounts every year for just rolling over the tenancy agreement. ~Jess

LikeLike